Ever felt totally lost trying to solve a math word problem?

Like you’re wandering around with no clue where to start?

That’s where the CUBES strategy jumps in to save the day – or does it?

This popular method has kids circling numbers and underlining questions like mathematical detectives.

Sounds helpful, right?

But here’s the plot twist: what if you’re circling the wrong numbers? What if this “foolproof” strategy is actually leading you astray?

Let’s dig into what CUBES really does, how it works, and why some teachers are starting to question if it’s helping or hurting.

Spoiler alert: the answer might surprise you!

What is the CUBES Math Strategy and How Does It Work?

Ever heard of CUBES?

It’s the math strategy that promises to make word problems way less scary.

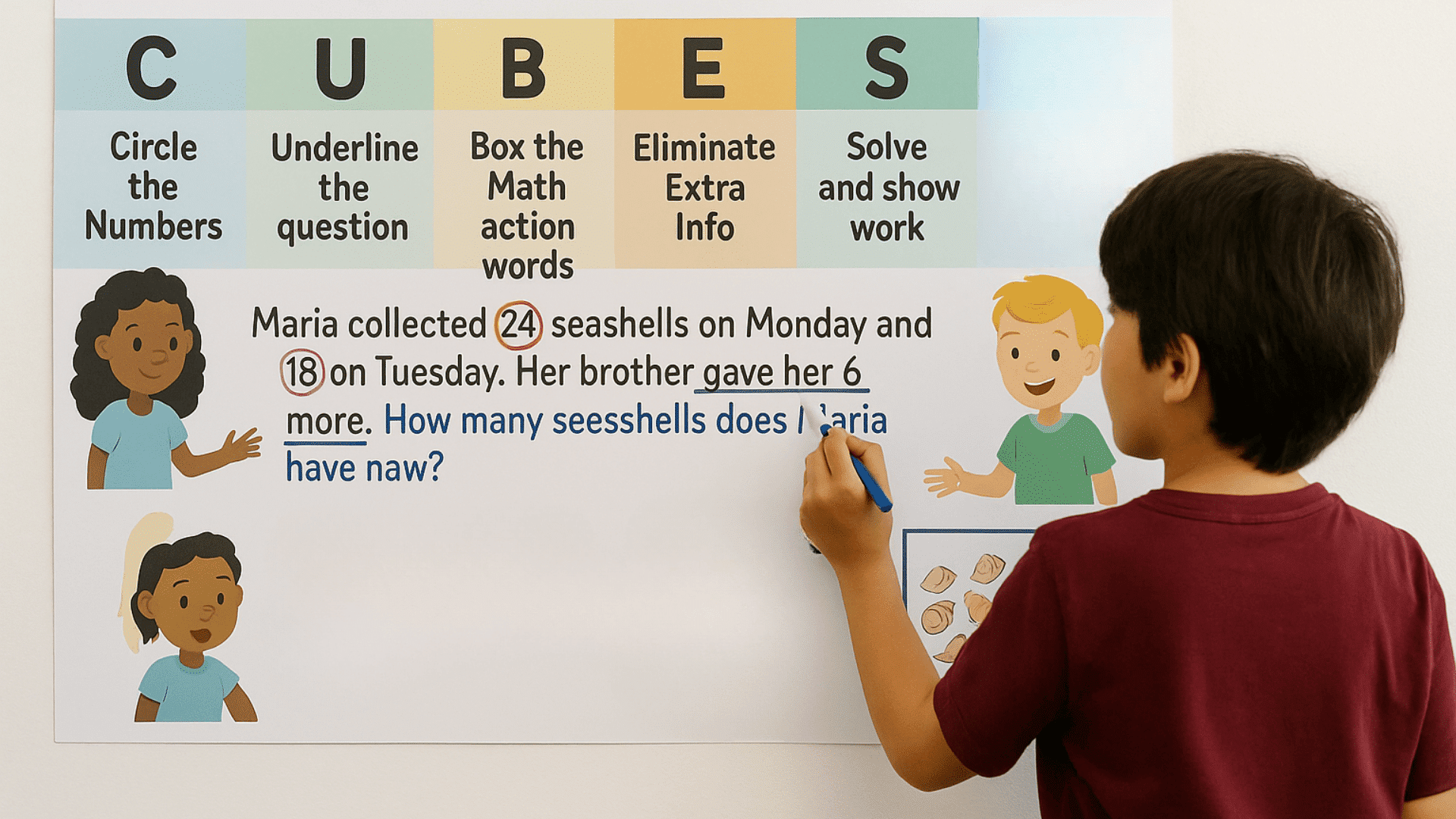

Here’s the deal: Circle numbers, Underline the question, Box action words, Eliminate extra info, and Solve while showing work.

Let’s try it!

“Sarah has 5 apples and buys 3 more. How many does she have?”

You’d circle 5 and 3, underline “How many,” box “buys more,” cross out unnecessary words, then solve 5+3=8.

This method took off in elementary classrooms during the early 2000s.

Teachers needed structured approaches for word problems.

It especially helped struggling students feel more confident.

Step-by-Step Implementation Guide for CUBES

While CUBES remains widely used, understanding its proper implementation helps identify both its intended purpose and inherent limitations.

These implementation details highlight where the method falls short of developing true mathematical reasoning.

Step 1: Circle the Numbers

Students identify and circle all numbers in the problem, including written numbers like “dozen” or “half.”

Many students mistakenly circle only digits, missing word-form numbers.

Teachers should emphasize that quantities can appear in various forms.

Practice with problems containing mixed number formats helps students recognize all numerical information.

Some students circle unrelated numbers like dates or ages when these aren’t relevant to the mathematical question.

Step 2: Underline the Question

The question sentence gets underlined completely, helping students focus on what they need to find.

Students often underline only part of the question or miss questions phrased as statements like “Find the total.”

Teaching students to look for question marks and command words improves accuracy.

Multi-step problems pose challenges when students underline only the first question they encounter.

Step 3: Box Math Action Words

Keywords suggesting operations get boxed: “altogether” (addition), “left” (subtraction), “each” (multiplication).

The biggest mistake occurs when students rely solely on keywords without considering context.

“More” doesn’t always mean addition; consider “How many more?” which requires subtraction.

Students need extensive practice recognizing when keywords mislead them.

Step 4: Eliminate Extra Information

Students cross out unnecessary details that don’t affect the mathematical solution.

Over-elimination remains problematic when students remove essential context.

In “Tom had 12 cookies for his party of 4 friends,” students might eliminate “party of 4 friends” when it’s needed for division.

Teaching careful reading prevents hasty elimination.

Step 5: Solve and Show Work

Students compute the answer and demonstrate their mathematical thinking through equations or drawings.

Common errors include rushing through computation after spending time on previous steps.

Students should verify that their answer makes sense within the problem context.

Encourage multiple solution strategies and clear work organization.

Example:

“Maria collected 24 seashells on Monday and 18 on Tuesday. Her brother gave her 6 more. How many seashells does Maria have now?”Circle: 24, 18, 6

Underline: “How many seashells does Maria have now?”

Box: “more”

Eliminate: (minimal extra information)

Solve: 24 + 18 + 6 = 48 seashells

Why Teachers Are Questioning the CUBES Method

The “number plucking” phenomenon describes students who grab numbers and operate on them without understanding the problem’s context.

CUBES inadvertently encourages this by prioritizing number identification over comprehension.

When students see “altogether,” they automatically add all circled numbers, even when logic dictates otherwise. Consider this problem: “Jake has 15 marbles.

He gives 7 to his sister and 3 to his friend.

His mom buys him 2 more packs with 6 marbles each.

How many marbles does Jake have altogether?”

Students often calculate 15+7+3+2+6=33, missing the multiplication and subtraction required.

Research-Based Criticisms of the CUBES Strategy

Powell, Namkung, and Lin’s 2022 study revealed that keyword-dependent students scored 23% lower on non-routine problems compared to those using comprehension-based strategies.

NAEP data shows declining problem-solving scores correlating with increased CUBES usage in districts.

The famous “shepherd’s age” problem: “A shepherd has 125 sheep and 5 dogs.

How old is the shepherd?” : demonstrates keyword strategy failure, with 75% of CUBES-trained students attempting meaningless calculations.

Research indicates only 60% success rates when problems contain misleading keywords versus 85% when students use sense-making approaches.

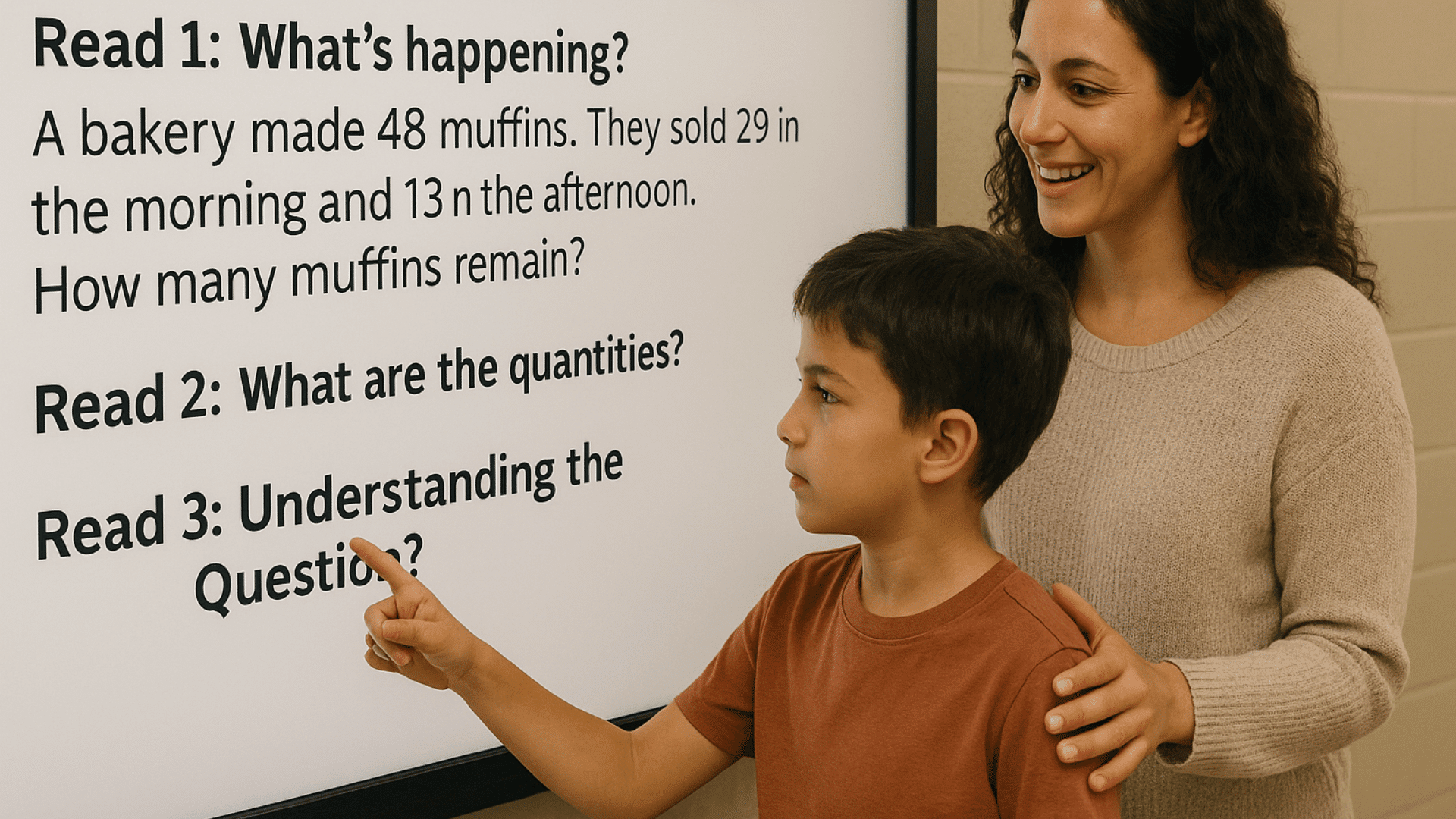

The Three-Read Protocol: A Smarter Way to Tackle Math Problems

Fed up with students mindlessly circling numbers and missing the point?

Many educators are switching to the Three-Read Protocol: a game-changing approach that actually builds understanding instead of just hunting for keywords.

Read 1: What’s the Story?

First read is all about the big picture.

Students forget about numbers completely and just focus on understanding what’s happening.

Who’s involved?

What’s the situation?

They might sketch it out or chat with a partner about the scenario.

Think of it as setting the stage before the math magic happens.

Read 2: What Are We Working With?

Now, students dig into the mathematical relationships.

What’s being measured?

How do these quantities connect?

Instead of just circling random numbers, they’re analyzing what each number actually represents and why it matters.

This builds real mathematical thinking, not just number-spotting skills.

Read 3: What’s the Real Question?

Finally, students get crystal clear on what they need to solve.

They put the question in their own words and plan their attack before jumping into calculations.

No more knee-jerk reactions to keywords!

See the Difference?

Take this problem: “A bakery made 48 muffins. They sold 29 in the morning and 13 in the afternoon. How many muffins remain?”

CUBES kids might circle all the numbers and add them up because they see “how many.”

Three-Read students understand the bakery started with 48, sold some throughout the day, and need to subtract: 48-29-13=6.

Alternative Problem-Solving Strategies That Build Critical Thinking

Making connections between math problems and reading comprehension strengthens overall understanding.

Just as students make inferences in literature, they should infer mathematical relationships.

The following strategies promote deep thinking rather than mechanical procedures.

| STRATEGY | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLE ACTIVITY | THINKING FOCUS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Notice and Wonder | Students list observations and questions | Given a problem, write “I notice…” and “I wonder…” statements | Encourages curiosity and careful observation |

| Drawing/Modeling | Visual representation of problem situations | Draw the problem before solving | Builds conceptual understanding |

| Acting Out | Physical demonstration of problem scenarios | Use students to act out sharing/grouping problems | Creates concrete connections |

| Manipulatives | Hands-on materials represent quantities | Use blocks for addition/subtraction stories | Supports multiple learning styles |

| Math Discourse | Structured mathematical conversations | Partner discussions about solution strategies | Develops mathematical language |

| Making Connections | Linking to real experiences | “When have you seen this in your life?” | Increases relevance and retention |

These approaches respect students’ thinking processes while building genuine problem-solving skills.

Unlike keyword dependency, they prepare students for varied problem types and real-world mathematical reasoning.

How to Transition Your Classroom Away from CUBES

Shifting away from the CUBES strategy can feel daunting, especially if it’s been a long-standing staple in your classroom.

To ease this change, consider a gradual rollout that prioritizes student understanding and reflection over rote procedures.

- Weeks 1–2: Introduce one alternative strategy alongside CUBES, allowing students to compare approaches.

- Weeks 3–4: Model thinking aloud without using CUBES keywords, emphasizing understanding over procedure.

- Weeks 5–6: Phase out CUBES anchor charts, replacing with sense-making prompts and question stems.

- Weeks 7–8: Full implementation of new strategies with student reflection on their problem-solving growth.

By pacing the transition over two months, you allow both you and your students to build confidence in new strategies while preserving a supportive learning environment.

Stay consistent and encourage open dialogue throughout the process.

Supporting Struggling Students Differently

Rather than relying on CUBES as a crutch, provide these scaffolds that build genuine mathematical understanding.

These supports address the root causes of confusion instead of masking them with procedural tricks.

Each strategy strengthens problem-solving skills while maintaining high expectations for all learners.

- Pre-reading vocabulary support for problem contexts

- Small group story problem discussions before individual work

- Concrete materials and visual models

- Peer partnerships for strategy sharing

- Modified problems with familiar contexts

These differentiated supports prepare students for long-term success in problem-solving.

Students develop confidence in their ability to make sense of new and challenging mathematical situations.

The Last Line

Remember that maze we talked about?

Turns out, CUBES might be leading you down the wrong path. Just because you circle numbers doesn’t mean you actually understand what’s happening in the problem.

Some students see circled numbers and automatically add them all up, even when they should subtract or multiply.

That’s like trying to solve a puzzle without reading the instructions!

Better strategies help you actually think through problems instead of just guessing.

Math isn’t about tricks or shortcuts; it’s about making sense of what you’re reading.

So next time, don’t just grab your highlighter.

Use your brain, too.

Curious minds don’t stop here, click here and check out more brain-boosting blogs that might surprise you!